Replacement of Large Equipment in Nuclear Power Plants

By: Julio Garcia, PhD, PE, Natalie Doulgerakis, PE, SE, Dan Parker, PE and Lachezar Handzhiyski

By: Julio Garcia, PhD, PE, Natalie Doulgerakis, PE, SE, Dan Parker, PE and Lachezar Handzhiyski

By: Andy Coughlin, PE, SE The modular construction industry is projected to grow globally at

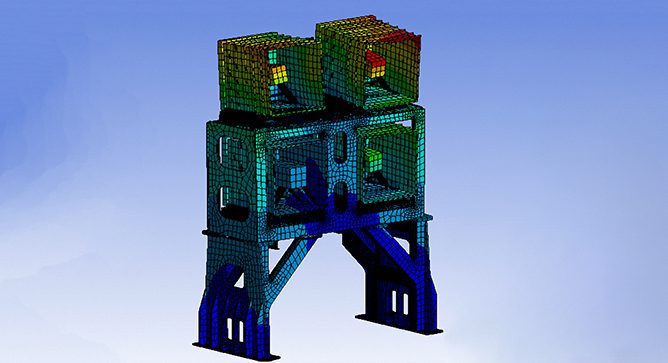

By: Dan Parker, PE By analytically simulating the steps in the construction process, including the

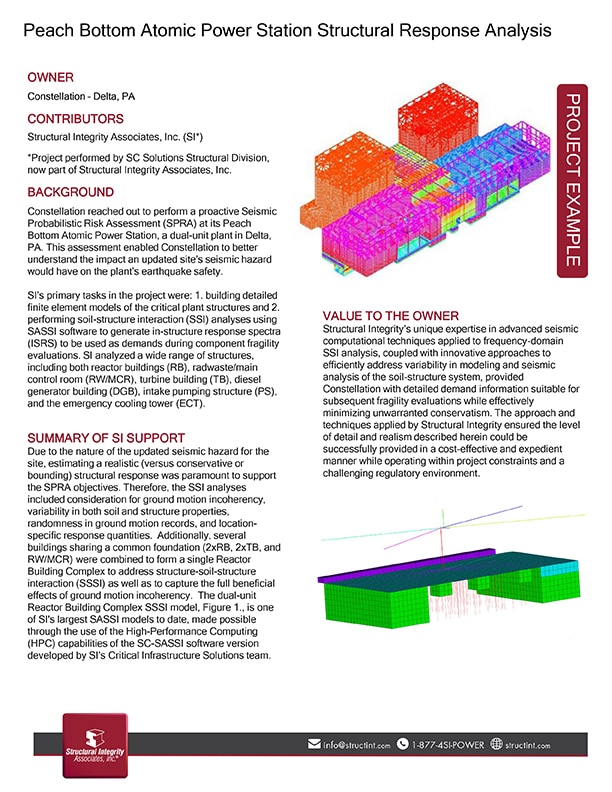

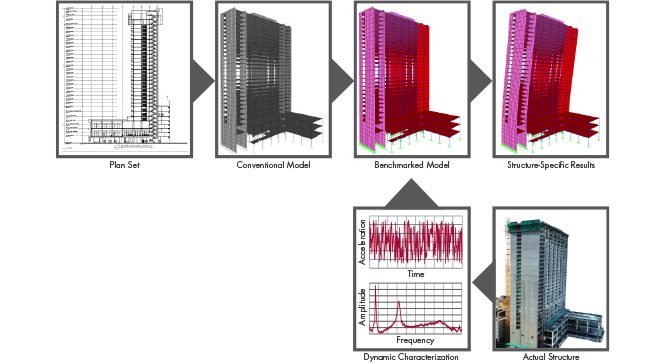

By: Eric Kjolsing, Ph.D., PE From 2015 to 2019 Structural Integrity Associates, Inc. (SI) worked

By: Eric Kjolsing and Dan Parker In 2018, Structural Integrity Associates (SI) supported a utility

By: Eri Kjolsing Introduction Structures may experience unforeseen operating environments or site-specific hazards leading to

By: Matt Tobolski Things change, that’s just a fact of life. But when it comes